Foucault, Madness and the Confusion

So madness has an affinity for water. Beautiful. Believe it or not this is Foucault.

"Renaissance men developed a delightful, yet horrible way of dealing with their mad denizens: they were put on a ship and entrusted to mariners because folly, water, and sea, as everyone then knew, had an affinity for each other. Thus, “Ships of Fools” crisscrossed the seas and canals of Europe with their comic and pathetic cargo of souls. Some of them found pleasure and even a cure in the changing surroundings, in the isolation of being cast off, while others withdrew further, became worse, or died alone and away from their families. The cities and villages which had thus rid themselves of their crazed and crazy, could now take pleasure in watching the exciting sideshow when a ship full of foreign lunatics would dock at their harbors."

Shocking. Lovely. An astonishing and revealing concept....except....., according to Scott Alexander:

"This was such a great piece of historical trivia that I was shocked I’d never heard it before. Some quick research revealed the reason: It is completely, 100% false. Apparently Foucault looked at an allegorical painting by Hieronymus Bosch, decided it definitely existed in real life, and concocted the rest from his imagination."

Well, back to the Foucault we all expected.

The "ship of fools" is an allegory, originating from Book VI of Plato's Republic, about a ship with a dysfunctional crew. According to Wiki:

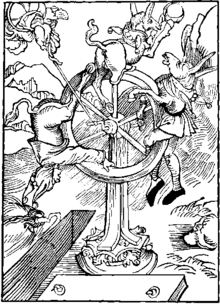

"The concept makes up the framework of the 15th-century book Ship of Fools (1494) by Sebastian Brant, which served as the inspiration for Hieronymus Bosch's painting, Ship of Fools: a ship—an entire fleet at first—sets off from Basel, bound for the Paradise of Fools. In literary and artistic compositions of the 15th and 16th centuries, the cultural motif of the ship of fools also served to parody the 'ark of salvation', as the Catholic Church was styled."

No comments:

Post a Comment